Why do some societies place a higher priority on forgiveness than others do? It is tempting to imagine that the differences come down to differences in religious values, but the group of nations that place the highest priority on forgiveness in their hierarchies of values includes Egypt, Ukraine, Vietnam, the United States, Australia, Japan, and Sweden—hardly a religiously homogeneous club. The same goes for the societies that place forgiveness relatively low in their value hierarchies: Canada, Turkey, China, Poland, Chile, India, and Israel are about as religiously varied as you could get.

So if it’s not religion that really matters, then what does?

The social psychologists Katje Hanke and Christin-Melanie Vauclair found a clever way to examine this question. They took advantage of existing published research that used the Rokeach Values Survey, which was first published in 1967. The Rokeach Values Survey asks respondents to rank-order two lists of values according to their personal importance. One of the lists comprises 18 so-called “instrumental values,” which Rokeach defined as “preferable modes of behavior.” The instrumental values are means to other ends–they’re people’s individual approaches to obtaining what Rokeach called the “terminal values” (this list, too, is a grab bag that includes “Wisdom,” “Salvation,” “National Security,” and everything in between). The Instrumental Values, then, are the means you use to fulfill the aspirations that matter most to you in life.

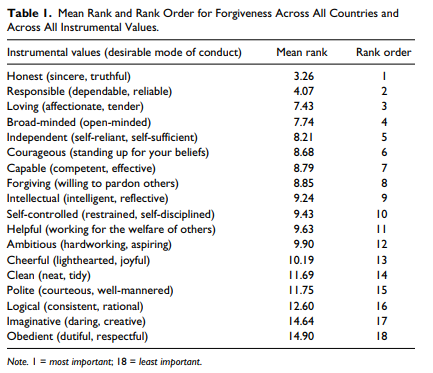

Hanke and Vauclair gathered up as many articles as they could find that used the Rokeach Values Survey between 1967 and 2006. With those articles in hand, they were able to estimate the value priorities of people in 30 different countries. Here’s a list of Rokeach’s 18 instrumental values and the mean rankings they received across all 30 nations. As you can see, on average “Forgiving” comes in right in the middle at #8:

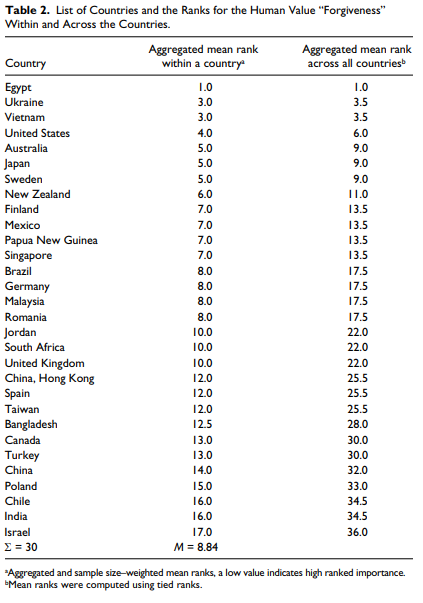

That average ranking is misleading, however, because as Table 2 shows, the 30 societies differed quite a lot in the priority they placed on forgiveness.

These cross-national trends are interesting enough, but the real value of this cross-cultural study comes from the researchers’ effort to examine the qualities of those societies themselves that determine the priority forgiveness receives. Hanke and Vauclair examined three measures in particular. The first was an index of human development that summarized information about mean life expectancy, national income per capita, and average level of educational attainment. The second was a measure of subjective well-being. The third was a measure of democratization.

The researchers found that societies that placed a relatively high value on forgiveness tended to have higher levels of subjective well-being and higher scores on the human development index. They were no more or less likely to be democracies. Moreover, when all three predictor variables were used simultaneously to predict the 30 nations’ prioritization of forgiveness, only the human development index emerged as a unique predictor of the importance ascribed to forgiveness. The societies in which people live long, fulfilling lives, it seems, are the ones in which people pursue forgiveness as a way of obtaining what matters most in life to them.

I find this conclusion to be particularly charming because it fits nicely with a body of theorizing called Life History Theory, which suggests that human beings adjust their approaches to life on the basis of whether they expect their lives to be long (vs. short), stable (vs. unpredictable), and mild (vs. harsh). When life is predictable and pleasant, people invest in the maintenance of thick, interconnected webs of social interaction that may not lead to personal payoffs for months, years, or even generations. In such an environment, it pays to forgive because forgiveness has the capacity to restore relationships that may pay out benefits over very long time horizons. When life is shorter, harsher, and less predictable, the theory goes, people have shorter fuses and defend their interests with threats of retaliatory violence. Such an interpretation also fits to some extent with some laboratory findings we have obtained about the role that early family environments might play in predisposing people to use revenge to defend their interests.

The study is not without its limitations. For some societies, for example, Hanke and Vauclair were able to find only a smattering of data upon which to make generalizations about an entire nation’s value profile over the course of 4 decades. Such estimates may contain much more noise than signal. Also, the authors they limited their search for possible society-level correlates of forgiveness to a rather limited number of possibilities. Still, it’s an admirable start. Given the tremendous attention that life history theory has been enjoying in recent years, and especially in light of the unceasing calls for social science to become a more self-consciously cross-cultural discipline, expect more work like this over the next decade.

Hanke, K., & Vauclair, C. M. (2016). Investigating the human value “forgiveness” across 30 countries: a cross-cultural meta-analytical approach. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(3), 215-230.