Altruism has been a major topic in evolutionary biology since Darwin himself, but altruism (the word) did not appear even once in Darwin’s published writings.[1] The omission of altruism from Darwin’s thoughts about altruism is hardly surprising: Altruism had appeared in print for the first time only eight years before The Origin of Species. The coiner was a Parisian philosopher named Auguste Comte.

Capitalizing on the popularity he had already secured for himself among liberal intellectuals in both France and England, Comte argued that Western civilization needed a complete intellectual renovation, starting from the ground up. Not one to shrink from big intellectual projects, Comte set out to do this re-vamping himself, resulting in four hefty volumes. Comte’s diagnosis: People cared too much for their own welfare and too little for the welfare of humanity. The West, Comte thought, needed a way of doing society that would evoke less égoisme, and inspire more altruisme.

Comte saw a need for two major changes. First, people would need to throw out the philosophical and religious dogma upon which society’s political institutions had been built. In their place, he proposed we seek out new principles, grounded in the new facts emerging from the new sciences of the human mind (such as the fast-moving scientific field of phrenology), human society (sociology), and animal behavior (biology).

Second, people would need to replace Christianity with a new religion in which humanity, rather than the God of the Abrahamic religions, was the object of devotion. In Comte’s new world, the 12-month Gregorian calendar would be replaced with a scientifically reformed calendar consisting of 13 months (each named after a great thinker from the past—for example, Moses, Paul the Apostle, Gutenberg, Shakespeare, and Descartes) of 28 days each (throw in a “Day of the Dead” at the end and you’ve got your 365-day year). Also, the Roman Catholic priesthood would be replaced with a scientifically enlightened, humanity-loving “clergy” with Comte himself—no joke—as the high priest.

Comte’s proposals for a top-down re-shaping of Western society didn’t get quite the reception he was hoping for (though they caught on better than you might think: If you’re ever in Paris or Rio, pay a visit to the Temples of Humanity that Comte’s followers founded around the turn of the 19th century). In England especially, the scientific intelligentsia’s response was frosty. On the advice of his friend Thomas Huxley, Darwin also steered clear of all things Comtean, including altruism.

Nevertheless, altruism was in the air, and its warm reception among British liberals at the end of the 19th century is how the word percolated into everyday language. It’s also why the word is still in heavy circulation today. The British philosopher Herbert Spencer, an intellectual rock star of his day, was a great admirer of Comte, and he played a major role in establishing a long-term home for altruism in the lexicons of biology, social science, and everyday discourse.[2] Spencer used the term altruism in three different senses—as an ethical ideal, as a description of certain kinds of behavior, and as a description for a certain kind of human motivation. (He wouldn’t have understood how to think about it as an evolutionary concept.)[3]

Here, I want to look at Spencer’s second use of the word altruism—as a description of a class of behaviors—because I think it is a deeply flawed scientific concept, despite its wide usage. At the outset, I should note that as a Darwinian concept—an evolutionary pathway by which natural selection can create complex functional design by building traits in individuals that cause them to take actions that increase the rate of replication of genes locked inside their genetic relatives’ gonads—altruism has none of the conceptual problems that behavioral altruism has.

With Spencer’s behavioral definition of altruism, he meant to refer to “all action which, in the normal course of things, benefits others instead of benefiting self.”[4] A variant of this definition is embraced today by many economists and other social scientists, who use the term behavioral altruism to classify all “costly acts that confer benefits on other individuals.”[5] Single-celled organisms are, in principle, as capable of Spencerian behavioral altruism as humans are. Social scientists who subscribe to the behavioral definition of altruism have applied it to a wide range of human behaviors. Have you ever jumped into a pool to save a child or onto a hand grenade to spare your comrades? Donated money to your alma mater or a charity? Given money, a ride, or directions to a stranger? Served in the military? Donated blood, bone marrow, or a kidney? Reduced, re-used, or recycled? Adopted a child? Held open a door for a stranger? Shown up for jury duty? Volunteered for a research experiment? Taken care of a sick friend? Let someone in front of you in the check-out line at the grocery store? Punished or scolded someone for breaking a norm or for being selfish? Taken found property to the lost and found? Tipped a server in a restaurant in a city you knew you’d never visit again? Pointed out when a clerk has undercharged you? Lent your fondue set or chain saw to a neighbor? Shooed people away from a suspicious package at the airport? If so, then you, according to the behavioral definition, are an altruist.[6]

Some economists seek to study behavioral altruism in the laboratory with experimental games in which researchers give participants a little money and then measure what they do with it. The Trust Game, which involves two players, is a great example. We can call the first actor an Investor because he or she is given a sum of money—say, $10—by the experimenter, some or all of which he or she can send to the other actor, whom we might call the trustee. The investor knows that every dollar he or she entrusts to the trustee gets multiplied by a fixed amount—say, 3—so if the investor transfers $1 to the trustee, the trustee now has $3 more in his or her account as a result of the investor’s $1 transfer. Likewise, the investor knows that the trustee will subsequently decide whether to transfer some money back. Under these circumstances, according to some experimental economists, if the Investor sends money to the Trustee, it is “altruistic” because it is a “costly act that confers an economic benefit upon another individual.”[7] But the lollapalooza of behavioral altruism doesn’t stop there: It’s also altruistic, per the behavioral definition that economists embrace, if the Trustee transfers money back to the Investor. Here, too, one person is paying a cost to provide a benefit to another person.

Notice that motives don’t matter for behavioral altruism. (To social psychologists like Daniel Batson, altruism is a motivation to raise the welfare of another individual, pure and simple. Surprising as it might seem, this is also, in fact a conceptually viable scientific category. But that’s another blog post.) All that matters for a behavior to be altruistic is that it entails costs to actors and benefits to recipients. Clearly, donating a kidney or donating blood are costly to the donor and beneficial to the recipients, but even when you hold a door open for a stranger, you pay a cost (a few seconds of your time and a calorie or so worth of physical effort) to deliver a benefit to someone else. By this definition, even an insurance company’s agreement to cover the MRI for your (possibly) torn ACL qualifies: After all, the company pays a cost (measured in the thousands of dollars) to provide you with a benefit (magnetic confirmation either that you need surgery or that your injury will probably get better after a little physical therapy).

But a category that lumps together recycling, holding doors for strangers, donating kidneys, serving in the military, and handing money over to someone in hopes of securing a return on one’s investment—simply because they all involve costly acts that confer benefits on others—is a dubious scientific category. Good scientific categories, unlike “folk categories,” are natural kinds—as Plato said, they “carve nature at its joints.” Rather than simply sharing one or more properties that are interesting to a group of humans (for example, social scientists who are interested in a category called “behavioral altruism”), they should share common natural essences, common causes, or common functions. Every individual molecule with the chemical formula H2O is a member of a natural kind—water—because they all share the same basic causes (elements with specific atomic numbers that interact through specific kinds of bonds). These deep properties are the causes of all molecules of H2O that have ever existed and that ever will exist. Natural kinds are not just depots for things that have some sort of gee-whiz similarity.[8]

If behavioral altruism is a natural kind, then knowing that a particular instance of behavior is “behaviorally altruistic” should enable me to draw some conclusions about its deep properties, causes, functions, or effects. But it doesn’t. All I know is that I’ve done something that meets the definition of behavioral altruism. Even though I have, on occasion, shown up for jury duty, held doors open for strangers, received flu shots, loaned stuff to my neighbors, and even played the trust game, simply knowing that they are all instances of “behavioral altruism” does not enable me to make any non-trivial inferences about the causes of my behavior. By the purely behavioral definition of altruism, I could show up for jury duty to avoid being held in contempt of court, I could give away some old furniture because I want to make some space in my garage, and I could hold the door for someone because I’m interested in getting her autograph. The surface features that make these three behaviors “behaviorally altruistic” are, well, superficial. Knowing that they’re behaviorally altruistic gives me no new raw materials for scientific inference.

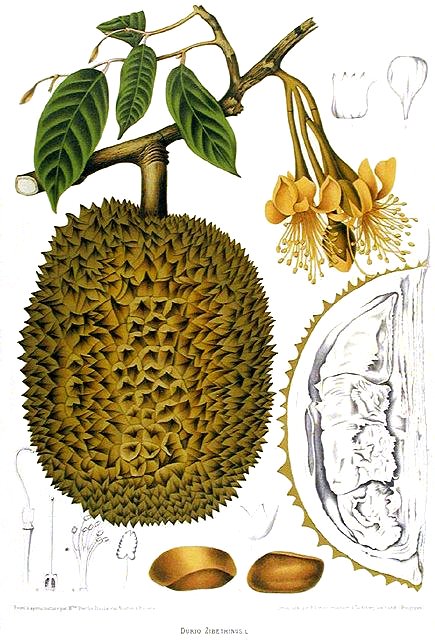

So if behavioral altruism isn’t a natural kind, then what kind of kind is it? Philosophers might call it a folk category, like “things that are white,” or “things that fit in a bread box,” or “anthrosonic things,” which comprise all of the sounds people can make with their bodies—for example, hand-claps, knuckle- and other joint-cracking, the lub-dub of the heart’s valves, the pitter-patter of little feet, sneezes, nose-whistles, coughs, stomach growls, teeth-grinding, and beat-boxing. Anthrosonics gets points for style, but not for substance: My knowing that teeth-grinding is anthrosonic does not enable me to make any new inferences about the causes of teeth-grinding because anthrosonic phenomena do not share any deep causes or functions.

Things that are white, things that can fit in a bread box, anthrosonics, things that come out of our bodies, things we walk toward, et cetera–and, of course, behavioral altruism–might deserve entries in David Wallechinsky and Amy Wallace’s entertaining Book of Lists[9], but not in Galileo’s Book of Nature. They’re grab-bags.

~

[1] Dixon (2013).

[2] Spencer (1870- 1872, 1873, 1879).

[3] Dixon (2005, 2008, 2013).

[4] Spencer (1879), p. 201.

[5] Fehr and Fischbacher (2003), p. 785.

[6] See, for instance, Silk and Boyd (2010), Fehr and Fischbacher (2003); Gintis, Bowles, Boyd, & Fehr (2003).

[7] Fehr and Fischbacher (2003), p. 785.

[8] Slater and Borghini (2011).

[9] Wallechinsky, Wallace, and Wallace (2005).

REFERENCES

Dixon, T. (2005). The invention of altruism: August Comte’s Positive Polity and respectable unbelief in Victorian Britain. In D. M. Knight & M. D. Eddy (Eds.), Science and beliefs: From natural philosophy to natural science, 1700-1900 (pp. 195-211). Hampshire, England: Ashgate.

Dixon, T. (2008). The invention of altruism: Making moral meanings in Victorian Britain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dixon, T. (2013). Altruism: Morals from history. In M. A. Nowak & S. Coakley (Eds.), Evolution, games, and God: The principle of cooperation (pp. 60-81). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425, 785-791.

Gintis, H., Bowles, S., Boyd, R., & Fehr, E. (2003). Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 153-172.

Silk, J. B., & Boyd, R. (2010). From grooming to giving blood: The origins of human altruism. In P. M. Kappeler & J. B. Silk (Eds.), Mind the gap: Tracing the origins of human universals (pp. 223-244). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Slater, M. H., & Borghini, A. (2011). Introduction: Lessons from the scientific butchery. In J. K. Campbell, M. O’Rourke, & M. H. Slater (Eds.), Carving nature at its joints: Natural kinds in metaphysics and science (pp. 1-31). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Spencer, H. (1870- 1872). Principles of psychology. London: Williams and Norgate.

Spencer, H. (1873). The study of sociology. London: H. S. King.

Spencer, H. (1879). The data of ethics. London: Williams and Norgate.

Wallechinsky, D., & Wallace, A. (2005). The book of lists: The original compendium of curious information. Edinburgh, Scotland: Canongate Books.

Might be time to see about having that Oxytocin tattoo removed…

Might be time to see about having that Oxytocin tattoo removed…